This is the first part of the epic (two-part) series of articles about tiny intros, the next one will be about an actual intro.

I love tiny graphical presentations called “intros” in the demoscene and by tiny I mean 256 bytes tiny. Usually, at this point people mention a paragraph of text is well over 256 bytes worth of data. However, you should not think that computer needs the same amount of data to store information such as “multiply variable X by variable Y” as we do. That textual representation needs 34 bytes of storage, less if you write it using shorter words or simply an equation. What a processor needs would be something like 3 instructions, 2-4 bytes each.

However, my point is that 256 bytes is ridiculously little for most people (even though you can hardly impress a mouth breather playing Halo 3 by stuffing amazing things in that space). At those sizes the source code is many times bigger than the resulting program. On the other hand, 256 bytes is plenty of space for those who are crazy enough to write such things. Why executables tend to be much, much bigger than that is because there is a lot of stuff in there what the programmer didn’t put in there himself/herself.

The Code

An obvious source of bloat in the executable is the fact programs are written in high-level languages such as C++ and then compiled into code that the processor can run. Compilers generally do a good job at producing working executables with fast code and they don’t even try to save space. Add tons of modern features – object polymorphism, runtime error checking et cetera – into that and you have your normal 100 kilobytes of code for the smallest program that necessarily doesn’t even do anything but exit back to desktop. On top of that, the executable file also houses information such as which libraries to use, the program icon and so on.

One way around the problem above – and it is a problem only if you for some reason are decided to spend you time doing something very few find nice – is to write the programs in more condensed languages. For example, C produces smaller code than C++ (thanks to the fact there is minimal extra fluff in C) and writing everything in assembly language produces pretty much as small code as it is possible to write because it basically is the human-readable version of machine language. A reminder: those modern languages (and C isn’t even modern as it was conceived in the 1970s) were created because writing complex things in assembly is not everyone’s cup of tea – that makes writing very tiny stuff in assembly not-everyone’s-cup-of-tea squared.

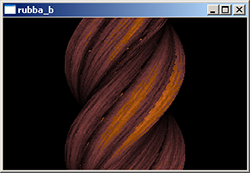

“rubba_b” by kometbomb…

… and the same for Windows – 254 bytes vs. 9278 bytes.

Another layer of arcane computing that makes a 256-byte executable possible is the use of old operating systems such as DOS. As you read above, the executable contains information about libraries and such, and back in the 80s hardly any shared libraries were used at all anyway. So, an executable pretty much was only the compiled program code and that was it. No extra fluff. Using this old executable format and assembly language the programmer essentially is the only factor that has any effect in the size of the executable.

Ironically, while old operating systems with no libraries do not provide any modern conveniences like fast 3D graphics or a mentionable interface to anything at all, this is a blessing. You can access the hardware directly which means a lot less code to do things like drawing a pixel on the screen. You don’t even have to set up those libraries because there isn’t any. As an example, the same intro (albeit converted to C code from assembly) in Windows XP is about 10 kilobytes in size, while the original version for DOS is less than 256 bytes. And, it would be even larger in Windows if it used the hardware to do the things it does in software.

The Data

Yet another reason why things like computer games or even larger intros are huge compared to the tiniest intros is because they come with a lot of precreated data like graphics and music. For 256-byte intros even a precreated flightpath for the camera is pretty much a no-go. Or, a 3D object with, say, more than four faces. That means we have to use procedurally generated data which is in the vogue right now even outside size restrictions, with things like Spore.

Actually, in many new school 256-byte intros the data is not even precalculated but simply calculated while the intro draws it on the screen. This is to save the space you would need if you had both the drawing loop and the precalculation loop (remember, even the loop structure uses precious bytes) – thanks to the fact even slow things are fast with a relatively new computer.

Speaking of slow things, one of them is raytracing. Which is purely mathematical, which means very little precreated material. Raytracing also is one way to produce realistic three-dimensional images, which as a rule of thumb, look nice. So, it’s not a surprise that a modern 256-byte intro uses raytracing, or raycasting, to simulate nature, look amazing and still fit in the specified size limit. If it’s 256 bytes and 3D, it probably uses some blend of raycasting. Older intros usually were versions of familiar 2D effects such as the rotozoomer, the fire effect, the Mandelbrot set and other well-explored routines.

The Art

Even among demo afficianados there is some controversy whether the tiniest intros have any merit as art or if they simply are a proof of concept of how small you can make something. There is no hidden gold vein as in nanotechnology in there. While most tiny intros are for the most part coder porn, nobody can deny their status as art installations. And if you stay in the 128-256 byte range, most of the popular tiny intros are quite pretty too, especially considering all the compromises that had to be made to make it fit.

The ultimate irony in downplaying the merits of the intros is that the demoscene pretty much was born from people pushing the machine to the limits. Well, nowadays to create a great demo (think of it as a large intro with many parts) you have to push your artistic talent more than the limits of the machines. It’s more like creating a music video, though, with your own tools. Seems like the final limit is the man-made limit of the smallest size you can fit something in and still call it art with a clean conscience.